Patients were randomized to receive either phenytoin or a placebo, with the primary outcome measure being the incidence of seizures within the first week and subsequently over the following two years. Results from this study demonstrated that while phenytoin effectively reduced the occurrence of early PTS compared to the placebo—markedly lowering the relative risk of seizure recurrence to 0.25 (95% CI 0.11–0.57)—it showed no significant long-term benefit in preventing later occurrences or improving overall outcomes. Despite its effectiveness in the acute phase, phenytoin did not influence the rate of late PTS, nor did it improve the long-term neurological outcomes, as assessed by subsequent evaluations of functional and cognitive recovery.

The application of phenytoin also highlighted some of the challenges associated with its use, including a well-documented side-effect profile. These side effects range from mild skin rashes to more severe forms such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Phenytoin also affects the hepatic enzyme system, leading to significant drug-drug interactions and necessitating close monitoring of blood levels to avoid toxicity. This prompted ongoing debates and further research into the safety and efficacy of such prophylactic treatments, guiding many subsequent trials aimed at refining the management of early PTS, making it a cornerstone study in neurotrauma care.

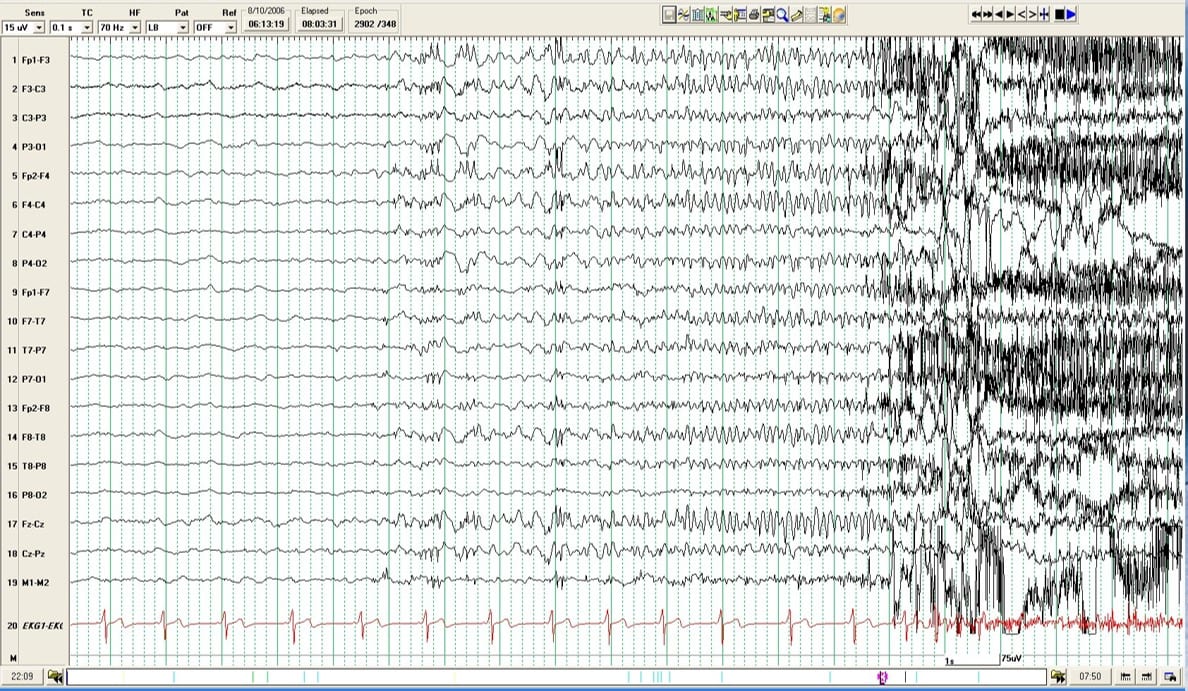

Fast forward to today, the treatment landscape for early PTS has evolved with more refined strategies. Levetiracetam has become preferred due to its favorable side effect profile compared to phenytoin. A study comparing levetiracetam and phenytoin found that the incidence of abnormal EEG findings was significantly higher in the levetiracetam group (p = 0.003) but showed similar efficacy in preventing seizure activity (p = 0.556). However, the debate continues, as some researchers argue for a more selective application of these drugs rather than broad prophylactic use, particularly highlighted in the latest guidelines which recommend anti-seizure medications only for high-risk patients to minimize unnecessary exposure to drug side effects.

While our approach to managing early PTS post-TBI has significantly advanced, it remains a field ripe for innovation. The original 1990 study laid the foundation over 30 years ago, and as we continue to refine our techniques and treatments, the goal remains clear: to enhance recovery and improve outcomes for moderate and severe TBI patients.

References:

- Temkin, N. R., Dikmen, S. S., Wilensky, A. J., Keihm, J., Chabal, S., & Winn, H. R. (1990). A randomized, double-blind study of phenytoin for the prevention of post-traumatic seizures. The New England Journal of Medicine, 323(8), 497-502. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199008233230801

- de Gans J, van de Beek D; European Dexamethasone in Adulthood Bacterial Meningitis Study Investigators. Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2002 Nov 14;347(20):1549-56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021334. PMID: 12432041.

- Jones, K. E., Puccio, A. M., Harshman, K. J., Falcione, B., Benedict, N., Jankowitz, B. T., … & Okonkwo, D. O. (2008). Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for seizure prophylaxis in severe traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgical Focus, 25(4), E3. https://doi.org/10.3171/FOC.2008.25.10.E3

- Pingue, V., Mele, C., & Nardone, A. (2021). Post-traumatic seizures and antiepileptic therapy as predictors of the functional outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury. Scientific Reports, 11, 4708. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84203-y